doi: 10.56294/pa202426

ORIGINAL

Misleading advertising of the food industry as a strategy to incentivize consumption even in the face of the enactment of the Junk Food Law

La publicidad engañosa de la industria alimenticia como una estrategia para incentivar el consumo aún frente a la promulgación de la Ley de Comida Chatarra

Joan Sebastián Noguera Cardona1 *,

Verenice Sánchez Castillo1 ![]() *

*

1Universidad de la Amazonia, Florencia-Caquetá, Colombia.

Cite as: Noguera Cardona JS, Sánchez Castillo V. Misleading advertising of the food industry as a strategy to incentivize consumption even in the face of the enactment of the junk food law. Southern perspective / Perspectiva austral. 2024; 2:26. https://doi.org/10.56294/pa202426

Submitted: 12-09-2023 Revised: 08-02-2024 Accepted: 17-04-2024 Published: 18-04-2024

ABSTRACT

Objective: to know the characteristics of misleading advertising in the food industry as a strategy to encourage consumption even with the enactment of the junk food law - 2021.

Method: qualitative, descriptive research is carried out with a family from the municipality from Pitalito in the department of Huila, the instrument used was the interview.

Results: the calorie intake of ultra-processed foods is an indicator of nutritional quality, these foods have a lower nutritional quality than fresh or minimally processed foods combined.

Discussions: nutrition messages that appear on food labels deserve special attention, due to misinformation and misleading advertising. Junk Food Project 167 of 2019 is aimed at improving this information.

Conclusions: it is necessary for the food industry to guarantee the full protection and prevalence of consumer rights. Various sectors of society and the government itself have mobilized in favor of the drafting of more restrictive legislation in relation to the advertising of unhealthy foods and beverages directed at children.

Keywords: Ultra-Processed Foods; Responsibility in Consumption; Artificial Additives; Health Effects.

RESUMEN

Objetivo: conocer las características de la publicidad engañosa en la industria alimenticia como una estrategia para incentivar el consumo aún frente a la promulgación de la ley de comida chatarra – 2021.

Método: investigación cualitativa, de tipo descriptiva, se realiza con una familia del municipio de Pitalito del departamento del Huila, el instrumento utilizado fue la entrevista.

Resultados: la ingesta de calorías de los alimentos ultraprocesados es un indicador de la calidad nutricional, estos alimentos tienen una calidad nutricional más baja que los alimentos frescos o mínimamente procesados combinado.

Discusiones: los mensajes sobre nutrición que aparecen en las etiquetas de los alimentos, merecen especial atención, debido a que la desinformación y la publicidad engañosa. El Proyecto 167 de 2019 de comida chatarra, se dirige a mejorar esta información.

Conclusiones: es necesario que la industria de alimentos garantice la plena protección y prevalencia de los derechos del consumidor. Varios sectores de la sociedad y el propio gobierno se han movilizado a favor de la elaboración de una legislación más restrictiva en relación a la publicidad de alimentos y bebidas no saludables dirigidas a los niños.

Palabras clave: Alimentos Ultraprocesados; Responsabilidad en el Consumo; Aditivos Artificiales; Afectación a la Salud.

INTRODUCTION

Nutrition messages that appear on food labels, deserve special attention, due to misinformation and misleading advertising that some food industries use to capture the attention of customers and achieve higher consumption of the products they promote, although it is the consumer’s right to have access to easy to understand information, companies make it difficult to read labels, when people consume an industrialized or ultra-processed food, they can not really know what they are eating just by reading the information on food labels, because the format and location of important information do not allow easy understanding, therefore, the improvement of nutritional labeling, is an important step to guarantee the consumer’s right to information and the promotion of healthier eating habits, in the labels according to the new junk food law of 2021 must appear the contents of sugars, sodium or fats, through a front warning seal, simple and clear, played a fundamental role in the formation of new eating habits in consumers (Garzón, Vega and Pineda, 2021).

This issue was first discussed at the international level in early 2010 when the Directing Council of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) approved the plan of action for preventing obesity in childhood and adolescence. The document defines four main lines of action to help countries reduce childhood obesity: promoting breastfeeding, better nutrition and more physical activity in schools, taxes on junk food and advertising restrictions, and greater access to recreational spaces and nutritious food (Cedeño, 2014).

Concerning marketing communication, the objectives are to enact regulations to protect children and adolescents from the impact of advertising of sugary drinks, low-nutrient energy products and fast foods and to institute standards for front-of-package labelling to facilitate quick identification of unhealthy foods.

According to García (2011), children in Mexico are unable to discern the persuasive intention of the advertising of foods and beverages of low nutritional value, which are associated with the risk of childhood overweight and obesity; therefore, countries should develop promotional campaigns that also help to control parents, because the lack of food information represents an ethical and human rights problem.

In turn, at the national level, according to the research conducted by Payan and Hernandez (2020), countries must adopt policies to reduce the exposure of children to the promotion and advertising of foods high in fat, sugar or salt to reduce the risks to children’s health and designate an agency to monitor, using a uniform set of indicators, the effects and effectiveness of policies on the exposure of children to promotion and advertising.

Likewise, according to Orjuela (2020), the vulnerability of the low-income population is an advantage for Marketing, which is increasingly expanding its range of strategies to attract investments from this public. In the case of ultra-processed foods, by covering the communication with visual and emotional appeals, endorsing celebrities, and showing business personalities with offers of gifts, they deceive the consumer who assures them that the food consumed is beneficial to their health.

In the departmental-level research conducted by López, Torres and Gómez (2017).it is specified that Marketing induces the excessive consumption of ultra-processed foods, and consequently, children have unhealthy eating habits since childhood. Thus, a package of snacks with a practically illusory nutritional value, besides being easier to transport and store, becomes more attractive and accessible than healthy food at a similar price.

For Ramírez (2020), this issue should be addressed locally in the city of Florencia Caquetá because all these foods promote childhood obesity, being that obese people are more prone to suffer from diseases such as arterial hypertension, liver cirrhosis, biliary calculosis, atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, diabetes, among others. In addition to this, there are psychological problems caused by obesity and malnutrition and their relationship with the decrease in life expectancy of people.

The problem to be addressed in this order of ideas is how misleading advertising leads to access to ultra-processed food, added to its wide dissemination through the continuous attraction of catchy advertisements, which constitutes a highly detrimental formula for healthy child development. As a result of a scenario of uninformed people, in addition to this, many children are reaching a growing scenario of overweight and obesity. Hence, there is a need to regulate advertising aimed at children, generating greater corporate commitments; food industries must commit to finding an effective solution. It is urgent to implement policies to combat obesity, malnutrition, and chronic diseases derived from it, as well as adopt effective instruments to support the regulation of food advertising, hence the relevance of this topic.

This research starts from the following problem question: What are the characteristics of misleading advertising in the food industry as a strategy to encourage consumption, even in the face of the enactment of the junk food law - 2021?

Theoretical Foundation

Junk food

Junk food is considered to be a certain group of ultra-processed foods rich in calories and low in nutrients, which, because of their ease of access, come packaged or are easy to prepare; commonly, this name often refers to foods sold in large chain food stores, such as sandwiches, french fries and pizzas. However, this concept also applies to other foods prepared quickly (Garcia, 2011).

Fast food culture came about in life with less time and more obligations. Thus, meals prepared in less than 10 minutes and extremely tasty became the main objective of the population; before the implementation of the fast food system, the moment of the meal and all its rituals had another meaning. Today, eating fast food or junk food is a new habit and still exerts an immense social fascination because while some see a need for this way of eating, others find pleasure, fulfilment, leisure and status in it (Garzón et al., 2021).

Responsible consumption and food advertising

There is a new profile of consumers concerned about the close relationship between food, health and disease, which has been demanding new market strategies for the food industries. Since the 1990s, these industries have been intensifying through advertising, the encouragement of the consumption of new products, including foods for special purposes, suitable for use in diets, differentiated or optional, that meet the needs of people with different metabolic and physiological conditions, in which changes in nutrient content are introduced. In this sense, there is also concern about products that contain complementary nutritional information, with the attribute light, or with specifications that provide energy or help children grow, when in fact they have excess sugars as is the mythical case of Milo and Chocolisto (Garzón et al., 2021).

Modern life, associated with the development of new technologies applied to the food area, boosted the increase in the consumption of industrialized products, easily accessible to pockets, packaged and ultra-processed; on the other hand, food industries are investing more and more resources in advertising their products, to conquer new and loyal consumers (Hernández, 2018).

Some reflections on communication and consumer perception

According to Rivera (2010), the written and audiovisual advertising message also constitutes a space for dialogue, where multiple interlocutors interact actively in the emission and reception poles, and the negotiation of interests marks the elaboration of advertising strategies.

The notion of communication as a space of negotiation is seen in a symbolic market; in this, social meanings are in permanent negotiation: they are produced, circulated and appropriated; the communicative practice can then be considered as the act of activating the productive circuit of social meanings, this market is operated by discursive communities that alter the message of their products by their way of perceiving, classifying and intervening in the world and society in search of symbolic power, the power to constitute reality.

Through this approach, the receiver/consumer is also always a producer of new meanings. In the context of public health, such a conception represents a break with the dominant communication model. Disruption implies health communication as a broad, complex, dynamic, polyphonic process operating in dialogic spaces characterized by divergences and the confrontation and negotiation of interests.

A practice arising from this conception would favour the active intervention of subjects in their realities, making them more capable of interacting with health risks and conditions. The first step to guarantee this possibility is the circulation of information that could not only be appropriated by the interlocutors but would also contribute to broadening their decision-making capacity; information is fundamental when seeking the participation of society and social control over public health policies, their priorities and forms of implementation. Thus, the right to information is inalienable from the right to health and its effective condition (Diaz, 2013).

Junk Food Law 2021

The Junk Food Law 2021 institutes the basic rules on food. It prohibits the dissemination of texts and advertising materials, whatever the vehicle used, for information contrary to those approved to appear on the label. Labelling is part of the recommendations promoted by international organizations such as the Pan American Health Organization and UNICEF; it must be clear, objective and reliable according to the guidelines in the technical regulations for food labelling. In this way, like labels, food advertising cannot induce the consumer to make mistakes, misunderstandings or errors; adequate information understood by the consumer will allow the act of consuming to generate a previous attitude of reflection on the need to consume and the risks on health, it must therefore be exposed when a processed food has excess sodium, excess sugars or trans fats (Project No. 167 of 2019).

METHODOLOGY

Location of the study

The research was conducted in the Rosales neighbourhood in the municipality of Pitalito in the Department of Huila, its territorial extension of 653km², its altitude of 1318 meters above sea level and its temperature (Villegas, 2019).

It was decided to conduct the research in this place for having the possibilities of collecting the information directly from the population, avoiding biases as much as possible, allowing a truthful approach to the perceptions of family groups about misleading advertising, the feeding of their children and the enactment of the Junk Food Law to improve the eating habits of minors.

Below is an image of the location of the municipality of Pitalito Huila, its extension and surrounding areas in order to contextualize the reader.

Figure 1. Map of Pitalito- Huila

Source: Google Maps

On the other hand, the Rosales neighbourhood belongs to Commune 2 of the locality; it is located within an area with a mediated commerce such as they are presented in a residential neighbourhood, with schools, neighbourhood stores, medium capacity supermarkets, where junk food sales are made because it is easily accessible for families (Villegas, 2019).

The population with which the study was conducted

It was chosen to conduct the research in the Rosales neighbourhood, which belongs to Commune 2 of the town of Pitalito-Huila; the research sample is a family living in the place, and the purpose was to know their perceptions, knowledge and eating habits that have been permeated by misleading advertising of junk food, for this purpose, an interview was conducted with one of the members of the household that allowed knowing what motivates them when choosing food for their children, the nutritional knowledge of these foods and their considerations about healthy eating and food safety (Villegas, 2019).

Research approach

This research was developed under the historical hermeneutic research paradigm, how the base is taken the interpretation of reality; in this sense of hermeneutics as a theory of knowledge, according to Dilthey (2018), helps to understand a daily process that accompanies all social action, it is a scientific method of knowledge construction that manages to transform pre-reflective knowledge to theoretical knowledge widely used in qualitative research as a starting point for theoretical-methodological reflections, but ended up developing new approaches, not only about the object to be studied but to the concept itself and the understanding of it.

The type of research was descriptive, where the researcher set out to know the reality without changing or intervening with it but only exposing and interpreting it; in this way, a logical analysis was performed to understand better what differentiates each particularity sought to incorporate and explain the being in the world, the challenges faced, the management of everyday language, in the understanding and meaning of their actions (Hernández et al., 2016).

On the other hand, the research was carried out under a qualitative approach, where it was intended to overcome the objectivism that claims privileged access to reality and, at the same time, achieve a rapprochement between the researcher and interviewee, in this order of ideas, qualitative research allowed knowing the realities and perceptions without making a numerical, measurable or measurable survey. However, it aimed to know the population under study by reflecting on their knowledge (Binda and Balbastre).

METHOD

In order to learn about the characteristics of misleading advertising by the food industry as a strategy to encourage consumption, the following guidelines were taken into account for interviews with key informants.

Families enrolled in the “Cero a siempre de Buen Comienzo” program in the municipality of Pitalito-Huila to learn about their and their children’s consumption characteristics.

In an initial review, they know what junk food is.

That they have been in the program for at least one year.

Once the interviewee is identified, we interview with open questions, considering the variables: misleading advertising of the food industry, consumption strategies, junk or packaged food, and eating habits in children and their families.

The interview was chosen because the participant could express his perceptions, thoughts and meanings constructed from his daily life. That of his family and children and the answers could be expanded as he interacted with the participant, who could express his opinions. The interview allowed the participant to narrate his anecdotes, and the researcher collected key information to achieve objectives through the interpretive reading of reality (Hernández et al., 2016).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The interviewee let us see ten categories of analysis in his story, which were grouped into the family of ultra-processed foods, as described below:

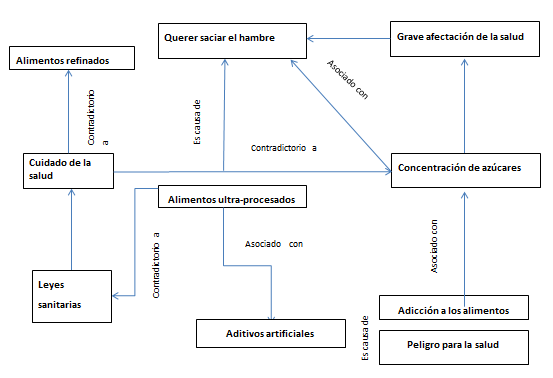

Figure 2. Ultra-processed food family

Ultra-processed foods are produced through a series of processes that modify the natural origin of the food by introducing artificial additives to add flavour and preserve the product, hence their meaning of “ultra-processed” because they contain few whole foods. According to the interviewee’s perception, these foods do not fulfil the function of nourishment; they are only consumed to satiate hunger, without providing nutrients to the body; typical examples include soft drinks and other sugary beverages, sweet and salty packaged snacks, as well as fast food and frozen meals (figure 2).

The consumption of these products is associated with a health hazard; these products are characterized by their convenience as they are durable and ready to consume, generating an addiction because they are loaded with flavours, sugars and presentations that are attractive to adults and children, since they have attractive packaging and dynamic marketing, being contradictory to the health laws in Colombia.

In line with what was raised by the interviewee, Garzón, Vega, and Pineda (2021) consider that the increase in the consumption of so-called ultra-processed foods is a global problem, and scientists from several countries have investigated the issue. They aim to determine whether there is a link between this type of food and consumer health problems.

Artisanal food processing and cooking have played an essential role in the evolution of mankind and the development of civilizations; however, the nature, degree and function of food processing have changed rapidly through industrialized food systems. Today, health problems related to industrial food processing are the subject of important debates in society and scientific communities worldwide; these current food processing practices negatively impact food quality, consumption patterns, health and well-being (Orjuela, 2017).

PAHO (2019) recommended that advertising and other food and beverage marketing aimed at children are rich in fats. These are special purpose foods, conceptualized as specially formulated or processed, in which changes in nutrient content are introduced, for the needs of immediacy in feeding children and people who, by their occupations, do not have the time or have the place to prepare their food according to their specific metabolic and physiological conditions, advertising of these foods must comply with the general provisions for food, provided in Bill 167 of 2019, known as junk food law.

A recent randomized clinical trial concluded that a diet with a strong focus on ultra-processed foods was associated with significantly higher energy intake and weight gain in children over two weeks, compared to a diet without ultra-processed foods; hence, the recommendations to limit consumption of highly processed foods and beverages (i.e., processed or prepared foods or beverages with excess sodium, sugars or saturated fats), because they are not part of healthy eating habits (La Republica, 2020).

Nutrition messages on food labels deserve special attention due to misinformation and misleading advertising that some food industries use to capture customers’ attention and achieve higher consumption of the products they promote. However, it is the consumer’s right to access easy-to-understand information; companies make it difficult to read labels. Project 167 of 2019, which regulates food marketing for children in early childhood, aims to regulate advertising and proper use of food.

According to Garzón, Vega and Pineda (2021), the calorie intake of ultra-processed foods indicates the overall nutritional quality of the diet; these foods have a lower nutritional quality than fresh or minimally processed foods combined with culinary ingredients. They are more energy-dense, rich in free sugars, sodium and saturated fatty acids and relatively low in protein, dietary fibre, vitamins and minerals.

Various sectors of society and the government have mobilized in favour of more restrictive legislation regarding the advertising of unhealthy foods and beverages to children. Faced with the strong pressure exerted by the economic interests of the food industries and the advertising sector, important actions designed by the government highlighted self-regulation; it is therefore expected that companies change their business practices and communication strategies aimed at children or even present their institutional commitments with the definition of nutritional criteria to guide public commitment (Ramirez, 2020).

The development of other research is recommended to help expand knowledge on the topic of responsible consumption and to help identify the effectiveness of the junk food law in the dietary practice of Colombian families.

CONCLUSIONS

This topic was inserted within a framework of special consumer protection, in which the consequences of food advertising and labelling are important to the Law. Likewise, this research aimed to address the problem of food advertising, which encompasses much of the advertising aimed at children, to study how advertising contributes to the incidence of poor nutrition and the responsibility to control abusive and deceptive practices used in marketing issues.

The food industry issues advertising offers and other related practices that should be regulated since there is the dissemination or promotion of foods with high amounts of sugar, saturated fats, trans fats, sodium and nutritional drinks with low content. Therefore, consumers have the right to clear and adequate information about the risks of excessive consumption of products that can contribute to a less healthy diet.

Responsible consumption and food advertising are interrelated issues. Currently, there is a new profile of consumers concerned about their health and that of their families; this has been demanding new market strategies for food industries; in Colombia, the struggle for responsible labelling of junk food has been forging since 2017, when a petition was raised based on scientific evidence exposing the risks of ultra-processed foods for health, currently the junk food law of 2021, is a start to control these abusive advertising practices, thus benefiting academia and civil society, families and especially the child population.

Being that Project 167 of 2019, known as junk food law in Colombia, is recent, there is little information about it being a topic little investigated and of vital importance since it provides knowledge on misleading advertising, the components of ultra-processed foods, the right to information of the Colombian consumer and awareness on the issue of healthy eating.

The food industry must guarantee the full protection and prevalence of rights that establish that it is the duty of the family, society and the State to watch over children and adolescents, with absolute priority, safeguarding their right to life, health, and food; therefore, advertising aimed at children consumers shows the concern of mentioning a certain topic since the child is in a phase of growth and, thus, is unprotected about consumption.

REFERENCES

1. Binda, N. U., y Balbastre, F. (2013). Investigación cuantitativa e investigación cualitativa: buscando las ventajas de las diferentes metodologías de investigación. Revista de Ciencias económicas, 31(2), 179-187.

2. Cedeño, R. M. (2014). Relación entre la obesidad y el consumo de comida chatarra en escolares de 5 a 10 años de edad atendidos en el Centro de Salud Dra. Mabel Estupiñán de enero a abril del 2013 (Bachelor’s thesis, Machala: Universidad Técnica de Machala).

3. De Cámara Proyecto 167 (2019). Por medio de la cual se adoptan medidas para fomentar entornos alimentarios saludables. Bogotá- Colombia

4. Díaz, C. G. (2013). Publicidad de alimentos y mensajes de salud: un estudio exploratorio. Ámbitos. Revista Internacional de Comunicación, (23).

5. Dilthey, W. (2018). Wilhelm dilthey: selected works, volume iv: hermeneutics and the study of history. Princeton University Press.

6. García, C. (2011). Los alimentos chatarra en México, regulación publicitaria y autorregulación. Derecho a comunicar, (2), 170-195.

7. Garzón, C., Vega, J., y Pineda, W. D. (2021). Influencia del consumo de alimentos ultra procesados promovidos a través de la publicidad engañosa en las condiciones de salud y los hábitos alimentarios en menores de 18 años en las localidades de Usaquén y Usme, de la ciudad de Bogotá.

8. Hernández, M. (2018). Análisis de la publicidad de alimentación infantil en las pantallas.

9. Hernández, R., Fernández-Collado, C. y Baptista, L.(2016). Metodología de la Investigación (4ta Edic). DF, México. McGraw Hill. Invitados especiales, 25(2), 95.

10. La República (2020). 60% de la población colombiana tiene malas costumbres a la hora de alimentarse. Disponible en https://www.larepublica.co/consumo/seis-de-cada-10-colombianos-no-saben-alimentarse-bien-2971569

11. López, G. A., Torres P, K., y Gómez, C. F. (2017). La alimentación escolar en las instituciones educativas públicas de Colombia. Análisis normativo y de la política pública alimentaria. Prolegómenos, 20(40), 97-112.

12. OPS (2019). Alimentos ultra-procesados ganan más espacio en la mesa de las familias latinoamericanas. Disponible en: https://www3.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=15530:ultra-processed-foods-gain-ground-among-latin-american-and-caribbean-families&Itemid=1926&lang=es

13. Orjuela, R. E. (2017). ¿Qué es la comida chatarra. Asociación colombiana de educación al consumidor, 4(1), 4-5.

14. Payan, A. D., y Hernández, D. (2020). Diseño de una secuencia didáctica para el abordaje del problema socio-científico del consumo de comida chatarra y sus efectos en la población escolar.

15. Ramírez, S. S. Estrategias y medios de vida para la seguridad alimentaria en el proceso de reubicación 2005-2010. El caso de la parcelación Andes Orteguaza en Florencia Caquetá.

16. Rivera, M. (2010). Reclaman por etiquetas y publicidad engañosa. Diario Extra.

17. Villegas, C. S. C. (2019). Plan estratégico de marketing territorial para el municipio de Pitalito Huila. Documentos de Trabajo ECACEN, (2).

FINANCING

The authors did not receive financing for the development of this research.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Joan Sebastián Noguera Cardona.

Data curation: Joan Sebastián Noguera Cardona.

Formal analysis: Joan Sebastián Noguera Cardona.

Research: Joan Sebastián Noguera Cardona.

Methodology: Joan Sebastián Noguera Cardona.

Drafting - original draft: Joan Sebastián Noguera Cardona.

Writing - proofreading and editing: Joan Sebastián Noguera Cardona.