doi: 10.56294/pa202425

ORIGINAL

Design of a local strategy for strengthening food sovereignty: the case of the el Pedregal municipal property of Villagarzón Putumayo

Diseño de una estrategia local para el fortalecimiento de la soberanía alimentaria: el caso del predio el pedregal municipio de Villagarzón Putumayo

Herlinton Alejandro Reyes Benavides1, Verenice Sánchez

Castillo1 ![]() *

*

1Universidad de la Amazonia. Florencia, Caquetá, Colombia.

Cite as: Reyes Benavides HA, Sánchez Castillo V. Design of a local strategy for strengthening food sovereignty: the case of the el Pedregal municipal property of Villagarzón Putumayo. Southern perspective / Perspectiva austral. 2024; 2:25. https://doi.org/10.56294/pa202425

Submitted: 09-09-2023 Revised: 05-02-2024 Accepted: 10-04-2024 Published: 11-04-2024

ABSTRACT

Introduction: the article discusses the evolution of global food systems, highlighting how advances in science, technology, and international markets have led to an automated food model. This model has increased food production to combat food insecurity, but has also generated significant negative impacts on the environment, communities, and human health. The persistence of food insecurity, the deterioration of arable land and the intensive use of agrochemicals are central issues. In Colombia, and specifically in Putumayo, agriculture is crucial to the economy, but faces challenges due to globalization and dependence on agrochemicals.

Methods: the study focused on the department of Putumayo, Colombia, specifically in the municipality of Villagarzón and the El Pedregal farm. Adopting a social critical approach, a non-experimental and descriptive design with a cross-sectional scope was employed, using interviews to collect qualitative data. The selection of key informants was based on criteria related to economic dependence on agriculture and recognition of agroecology as an alternative method.

Results: the interviews revealed a perception of food sovereignty as an expression of independence in agricultural and livestock production. Challenges identified include the need for investment and incentives, overcoming cultural barriers and the importance of effective technical advice. Technology transfer, focusing on integrated pest management and the use of on-farm inputs, was highlighted as crucial for the transition to agroecological practices. Challenges include overcoming cultural and economic constraints and the need for committed, quality advice.

Conclusions: strengthening food sovereignty in Villagarzón, Putumayo, requires a local strategy that promotes producer independence, encourages internal production, and ensures the commitment and active participation of both producers and technicians. Complementarity, understood as collective work to obtain and govern resources and capacities, emerges as a key to the sustainable development of the agricultural community. The importance of quality technical assistance and a focus on agroecology is emphasized.

Keywords: Food sovereignty; Agroecology; Food security; Agrochemicals.

RESUMEN

Introducción: el artículo discute la evolución de los sistemas alimentarios globales, destacando cómo los avances en ciencia, tecnología y mercados internacionales han llevado a un modelo de alimentación automatizado. Este modelo ha aumentado la producción de alimentos para combatir la inseguridad alimentaria, pero también ha generado impactos negativos significativos en el medio ambiente, las comunidades y la salud humana. La persistencia de la inseguridad alimentaria, el deterioro de tierras cultivables y el uso intensivo de agroquímicos son temas centrales. En Colombia, y específicamente en el Putumayo, la agricultura es crucial para la economía, pero enfrenta desafíos por la globalización y la dependencia de agroquímicos.

Métodos: el estudio se centró en el departamento de Putumayo, Colombia, específicamente en el municipio de Villagarzón y la finca El Pedregal. Adoptando un enfoque crítico social, se empleó un diseño no experimental y descriptivo con un alcance transeccional, utilizando entrevistas para recopilar datos cualitativos. La selección de informantes clave se basó en criterios relacionados con la dependencia económica de la agricultura y el reconocimiento de la agroecología como un método alternativo.

Resultados: las entrevistas revelaron una percepción de la soberanía alimentaria como una expresión de independencia en la producción agrícola y pecuaria. Los desafíos identificados incluyen la necesidad de inversiones e incentivos, superación de barreras culturales y la importancia de una asesoría técnica efectiva. La transferencia de tecnología, enfocada en el manejo integrado de plagas y el uso de insumos internos de la finca, se destacó como crucial para la transición hacia prácticas agroecológicas. Los retos incluyen superar limitaciones culturales y económicas y la necesidad de un asesoramiento comprometido y de calidad.

Conclusiones: el fortalecimiento de la soberanía alimentaria en Villagarzón, Putumayo, requiere una estrategia local que promueva la independencia de los productores, fomente la producción interna y asegure el compromiso y la participación activa tanto de los productores como de los técnicos. La complementariedad, entendida como el trabajo colectivo para obtener y gobernar recursos y capacidades, emerge como clave para el desarrollo sostenible de la comunidad agrícola. Se subraya la importancia de la asistencia técnica de calidad y un enfoque hacia la agroecología.

Palabras clave: Soberanía Alimentaria; Agroecología; Seguridad Alimentaria; Agroquímicos.

INTRODUCTION

A food system “is composed of elements such as the environment, populations, resources, institutional and infrastructural processes and activities related to the production, processing, distribution, preparation, and consumption of food, as well as the results of these activities on nutrition and health status, socioeconomic growth, equity, and environmental sustainability” (Soares. 2020, p.21 ) the continuous advances in science, technology and the international market have opened the way to an automated and universal food model that automates agriculture leading to an intensification of yields, increased use of chemicals and machinery as well as industrialized food processing. (Ceccon, 2008) This model increased food production to combat food insecurity in developing countries. However, its negative impact has relevant effects on the environment, community life, and people’s health.

Recent research assures that the progress achieved in human development has been evident in the problems of hunger and malnutrition, thanks to the increase in food production; but at the same time, works such as that of Ramos 2007 assure that more than a tenth of the world’s inhabitants still do not have the food they need (p.3 ) which reflects a high rate of food insecurity that is still in force, the increases in agricultural production advance with the development of technology, deteriorating arable land and the use of inputs outside the production system; which contracts the disappearance of resources such as natural control, which directly affects the environment and health of producers; which is increasingly vulnerable (Alvarez, 2019). The adoption of intensification has changed the natural, peasant, and mechanical control methods for the control of diseases, weeds, and pests by pesticides; in the same way, mineralized fertilizers of chemical synthesis have supplanted manure fertilizer, controlled decomposition, and leguminous crops; this without taking into account the mechanisms of technified tillage that aggravate the situation and the world population is still suffering from hunger. The products external to the production systems are considered agrochemicals and are the chemicals used to protect crops from diseases and pests (Ilo, 2003, p. 5), which are severely questioned because of their effects on the environment and the health of those who handle them; according to the Environmental Protection Agency of the United States EPA (2002), more than half of the intoxications in that same year in the agricultural environment were caused by the use of agrochemicals.

Agriculture is the basis of rural income in Colombia; it considerably strengthens national income, poverty eradication, food security, and sustainable development, according to Rafael Mejía López, President of the Sociedad de Agricultores de Colombia (SAC).

“In the last ten years, it has contributed one-tenth of Colombia›s gross domestic product, and in more than half of the departments, it is one of the most important activities in the GDP. On the other hand, there are 3954109 hectares of agricultural land in Colombia, of which 1597000 are short cycle and the permanent ones amount to 2356000 hectares. All these hectares produce 24 million tons of food, and livestock production produces 3’721,000 tons for 27721000 tons”. (p.22)

However, not everything is positive; with the opening to the globalization of the capitalist food system and the free trade agreements (FTAs), small and medium producers dedicated to family farming are affected, as they lack technological innovations, money, and sufficient training, reducing their competitiveness and producing significant impacts on the economy, security and food sovereignty of these families. Not to mention issues such as the high inequality in income distribution (Castellano, 2012, p.22).

The department of Putumayo has an economy represented to a large extent by agriculture, the main crops being “banana, cassava, corn, rice, potato, beans, sugar cane and palm heart, and fruit trees such as chontaduro, pineapple and chiro, mainly” CORPOAMAZONIA, (2011, p.24 ), production in the department is conventional and is closely related to the use of agrochemicals for fertilization and the management of pests and viruses, fungi and bacteria that affect crops. The livestock sector is growing relatively fast in the department. Its management has been generalized regarding animal feed based on products from outside the farm, mostly purines and concentrates, based on production in less time (CORPOAMAZONIA, 2011, p.24).

The municipality of Villagarzón is known for its large chontaduro harvest and is recognized by several magazines as the world capital of this fruit; however, it also stands out for the production of Musaceae, citrus, pineapple, Yota, yucca, Amazonian fruits, and camaron grapes, all of which are produced under a conventional model based on the use of agrochemicals, in addition to livestock production of pigs, dual-purpose chickens, dual-purpose cattle, guinea pigs and rabbits, among others.

The El Pedregal property is in a state of agricultural and livestock production with facilities such as sheds and corrals. It sheds for livestock production in addition to housing and farmland. Production management and practices are very conventional and depend on agrochemicals and purines to protect insects, viruses, fungi, bacteria, and animal feed. Likewise, there is a great dependence on the market to purchase food from the family of producers.

Evidencing the problem of food insecurity of the family of producers and the great dependence on agrochemicals that are being unleashed and knowing the model that promotes it and the consequences behind it, it is necessary to design a local strategy to strengthen the food sovereignty of the family, through the active disposition, willingness, and interest of producers, based on agroecology as an alternative model that combats dependence on agrochemicals and purines, helps in the construction of territory and cares for the environment in order to understand the alternatives to the conventional capitalist system.

Based on the above problem, the research development of this work is directed to answer the following question: What elements should be integrated into a local strategy that contributes to the strengthening of food sovereignty?

Justification

What we want to achieve with this document is to contribute to food sovereignty, studying the axes of application of the same to generate alternatives to strengthen food sovereignty in the municipality of Villagarzón Putumayo.

It is important to strengthen the food sovereignty of the producers of the El Pedregal farm to avoid dependence on external products to the productive unit and thus provide the development of agroecological techniques that help the food sovereignty of the family and the decentralization of the conventional system as the only production model.

Thus, providing information about new models of alternative production because the fact of producing or generating alternative products without damaging the environment also contributes to food sovereignty because the communities would be feeding themselves with healthy, safe products of responsible consumption, which favor the environment, which can generate surpluses and guarantee access to food; which strengthens the farm system.

A local strategy is important to carry out firstly because the producers will participate in the design and secondly because from this, the producers will have a clear line or route on how to strengthen their food sovereignty, and this contributes effectively so that small producers in the medium and long term can improve their production schemes with the generation of some surpluses, gaining importance and support from government entities.

Theoretical framework

Food sovereignty

Food sovereignty has been highlighted with great interest after the food price crisis in recent years because, unlike food security, which is only interested in obtaining food at all times, food sovereignty focuses on the legitimacy of people to a balanced and adequate food and the ability to choose the ways of handling, processing, distribution, and consumption of food. In this environment, food sovereignty embraces the ends of food security and sustainable development, making it a new topic for debate.

Evolution of the concept:

The definition of food sovereignty has been in constant change since several years ago when (Via Campesina 1996, cited in Windfuhr & Jonsén, 2005) supported it as: The legitimacy of each territory is to maintain and advance its food production schemes, which are important for feeding the country and the communities.

Went through numerous discussions until the (Peoples’ Food Sovereignty Network 2002 cited in Bringel, B. 2015) defined it as: A priority for countries and peoples to draft their own agricultural, employment, food, and land policy regulations in a way that is environmentally friendly and socially, economically, and culturally appropriate.

Finally, the statements of Nyeleni & Selingué (2007), which consider food sovereignty as: “A people’s right to balanced and culturally accepted, accessible food produced sustainably and ecologically and their right to choose their own food and production system” (p.25).

Axes of application of food sovereignty. Ortegam M., & Rivera, M. (2010)

· Obtaining resources: This axis promotes and assists in group and individual exercises for the entry and management of benefits (land, seeds, credit, etc.) in a profitable manner, promoting community rights and highlighting women’s access to resources.

· Forms of production: Support is given to local, family-based, and diversified systems that promote a sustainable and culturally accepted agricultural and livestock production model.

· Processing and sale: The right to market the products obtained by farmers, workers, shepherds, etc., to feed the local population is defended, so short marketing circuits are carried out.

· Self-consumption and legitimate food: This protects the right to healthy, balanced, and accepted food from autochthonous and local products obtained through agroecological techniques.

· Agrarian policies: Defends the right to peasant participation in structuring public policies related to food sovereignty.

Objective and scope

When the peasant social movement Via Campesina (1996) first discussed the term food sovereignty at the World Food Summit through the declaration “Food Sovereignty, a future without Hunger,” it did so to study new alternatives to those established by the neoliberal system to achieve food security. At the same time, this welcomed alternatives to world trade policies and would formalize legitimate food (Windfuhr & Jonsén, 2005, p. 57).

Therefore, based on the concept of food sovereignty given by Via Campesina (1996 cited in Windfuhr & Jonsén, 2005), the main objectives and scope of food sovereignty are the following:

· Food, a Basic Human Right: In this objective, the scope is to ensure that each territory allows food to be legitimate and allows the progress of the agricultural and livestock sector to fulfill this fundamental right. In addition, food must be balanced, abundant, and of adequate quality to sustain an active and dignified life and must not cause harm to the body.

· Agrarian reform: The objective of a true agrarian reform proposes the scope of giving people, especially women, control over productive land that they work, free of any discrimination, to small producers to provide them with credits, technologies, markets, and extension services to achieve the appreciation of the countryside economically and socially and finally to derive more investment in ecologically adequate rural roads.

· Protection of Natural Resources: The scope of this objective is to provide sustainable systems that do not affect the earth’s resources (land, water, seeds, and animal breeds) by avoiding the use of agrochemicals, single-species cash crops, and intensive systems in order to preserve biological diversity. Communities are free to use and protect their seeds and animal breeds.

· Reorganization of trade: This objective aims to ensure that national agricultural policies prioritize national production and consumption within the same territory and achieve food self-sufficiency. Local products must stand out over imports. Small productive units should produce food for the family basket and have autonomy in the prices of their products, which will be profitable.

· Eliminate the globalization of hunger: This objective aims to achieve “the regulation and taxation of speculative capital and strict compliance with a code of conduct for TNCs” Via Campesina (1996 cited in Windfuhr & Jonsén, 2005).

· Social Peace: This objective states that food will not be used as a defense mechanism, rejecting situations of repression and oppression.

· Democratic Control: guaranteeing the participation of small producers in formulating new agricultural standards at all levels. Achieving democratization of the UN and providing accurate and frank information to make open and democratic decisions with a greater focus on women.

Food sovereignty assessment methodologies

Based on the concept of food sovereignty given by Via Campesina, (2009, cited in Silva, 2013).

A community (people, countries, regions, etc.) has food sovereignty when they prioritize organization, productivity, and consumption according to local requirements and protect the domestic market from low-cost imports from other territories in their own right through agricultural and food policies that they have determined. Where small producers have access to the necessary resources (p.22).

Food sovereignty is evaluated through a panel of indicators defined based on a categorical structure, taking in large concepts and breaking them down into subcategories to cover all the main themes in the discourse of food sovereignty (Ortega., Rivera 2010, p.4).

This is shown by Sanchez (2018) in his study Seguridad y soberanía alimentaria en la agricultura familiar campesina: el caso de los agricultores de Tibasosa, Turmequé y Ventaquemada, Boyacá where he managed to determine the categories and subcategories that would be used as study variables to give fulfillment to the specific objectives from some research tools.

Understanding then, food sovereignty is a right of communities (people, countries, regions, etc) to determine their agricultural and food policies, prioritizing the organization, productivity, and consumption according to local requirements and safeguarding the domestic market from low-cost imports from other territories. Where peasants and small farmers must have access to necessary resources (land, water, and seeds), productive resources, and public services making it clear that food sovereignty and sustainability are more important than trade policies Via Campesina, (2009, cited in Silva, 2013) and that it embraces the purposes of food security and sustainable development, the evaluation methods can be determined based on the five categorical axes that define food sovereignty and that these, in turn, can be studied through subcategories that are seen as Indicators.

Local strategies

The procedure with which it is intended to provide solutions to a problem, before being put into practice, must be contextualized, defined, and compared in order to provide a guiding thread for the study, which is why local strategies are presented below as the actions or procedures aimed at providing a solution to the problem studied. Likewise, knowing the types of strategies that can be used in the locality helps us understand how local planning is concretized in practice.

Concept: The idea of strategy is quite old and is directly related to aspects related to the territory. It prioritizes actions according to the incidence or importance during the plan’s development, from greater to lesser. When designing a strategy, it is necessary to take into account that it must have a connection between the environment and the resources of the territory; it must also rescue a unique characteristic of the territory and must be dynamic, flexible, sustainable over time, and able to adapt to changing situations. Silva (2017)

FAO (2009) defines local strategy as a strategy designed for application to the local and specific needs of a specific local area or community.

Different strategies can be developed at the local level, allowing an understanding of the intervention mechanisms in which local planning is developed. According to Silva, I. (2017), the following local strategies are differentiated:

· Complementarity strategies: In these, there are the elements and actions that generate development in the locality studied to promote alternatives for the benefit of the same; some elements are the complementation between actors, products, municipalities, etc.

· Consolidation strategies: These are intended to expand the benefits of those services found in the locality; an example is improving education.

· Diversification strategies: These are intended to implement new, alternative, and improved mechanisms different from those already existing in the locality.

· Recovery and revaluation strategies: This strategy is developed in localities where resources are about to be exhausted and are used to reorient to the production of new products and services within the locality.

· Rebalancing strategies: These are used to reduce differences and inequalities within the locality.

Strengthening

Understanding the purposes of a strengthening strategy helps us develop methodologies and activities on which we can rely to achieve the strengthening process. These methodologies and activities allow us to give direction and control of the circumstances of the environment to achieve collective and personal welfare. That is why studying the perception of strengthening, the scopes or objectives, and the methodological forms of evaluation is of great importance for developing this work.

Concept

For Montero (2009), empowerment is supported by community activities such as participation, awareness, control, self-management, and commitment, which are the most important in the empowerment process. Taking these aspects into account, for this paper, empowerment is understood as the process through which the individuals of a locality (interested members) obtain group competencies and support material to complement their life situation towards development, acting with commitment, awareness, and self-evaluation, to enable them to transform their environment according to their needs and aspirations.

Strengthening objectives: Likewise, Montero (2009) defines that the main objectives of strengthening are evidenced when:

· There is a focus on living conditions and a greater mastery of the local circumstances.

· There is a command over the means used to achieve the proposed change within the environment.

· Overcoming oppression and exploitation and more egalitarian relations are achieved.

· The conditions that generate the problems are overcome.

Evaluation and follow-up strategies and methodologies

When the proposed goal is to strengthen, Bartle (2007) indicates that “measurement and definition are strongly related, and that we can study the concepts of strength, power or capacity applied to the community, examine its various components and identify the set of references that will indicate when there has been an increase in the power or capacity of these” (p.3).

This means that the people who make up the community must be aware that the objective is their empowerment and the aspects that affect its achievement, which is why Bartle (1987) indicates that it is relevant that the people of the community group under study participate in the evaluation of their empowerment, and that the facilitator should provide benefits and design a method to initiate a control method to achieve a consensus in the evaluation.

Therefore, it is understood that a strengthening process is only achieved within the studied community. However, it is a process carried out from within the communities so that they can obtain and manage resources and capacities to achieve collective developments and transformations in terms of their quality of life. This is because when we start a strengthening process, we must know the condition of the community, its degree of organization, participation, and commitment. This strengthening is achieved through self-evaluation methods or using a guided discussion.

METHOD

Location

The study was developed in the Amazon region of Colombia in the department of Putumayo, a representative place for its great wealth of environmental resources, in addition to a climate that benefits the conditions for planting and crop production, besides having a comparative advantage in water resources that favors the establishment of supply and environmental services. Bolaños (2015 p.3)

The municipality of Villagarzón, according to Burbano (2018), is located in a region that shares the climatic conditions of the Amazonian Piedmont. In this area, two different wind currents are found and cause the decantation of rainfall, which is changed by the vegetation cover and soil profile structure, which produce high evaporations that cause increases in the humidity levels of the adjacent atmosphere.

Because of its geographic location, the municipality of Villagarzón has a tropical rainy climate, with temperatures between 25°C and a relative humidity of 66 %. Mayor’s Office of Villagarzón (2020, p.160)

Figure 1. Map Municipality of Villagarzón, department of Putumayo

Source: (Burbano, 2018)

The case study was conducted in the rural area of Villagarzón in the village of San Isidro on the farm el pedregal owned by Ricardo Zenón and his wife Adriana Rojas and children, which is located 7,8 km from the municipal seat 15 minutes 0°59’48.9 “N 76°34’47.1 “W.

Figure 2. Location Vereda San Isidro, El Pedregal, Municipality of Villagarzón

Source: (Google Maps)

Methodological approach

This manuscript was based on the critical social paradigm because it is intended to address the needs related to food sovereignty of the producers of the Pedregal farm, which is in line with the concept of Agilar (2012), who indicates that the critical social paradigm allows us to describe and transform the context since it not only helps us to generalize data or understand the realities but also allows us to carry out social transformations in the area where it operates. Therefore, designing a strategy for strengthening food sovereignty by studying the axes of its application allows us to carry out social transformations in the producers through the way of producing, the use of time and space, and the implementation of appropriate and accepted technology.

The research was based on the theoretical guidelines proposed by Hernández-Sampieri (2018). Therefore, the design that was developed is of a non-experimental type supported by the fact that there was no manipulation of variables; in line with the above, the scope is descriptive transactional, which allowed the researcher to learn about the properties and features of the productive unit studied, where the research instrument to be applied is an interview where qualitative information is collected, thus concluding that the approach of this research is qualitative.

Method

To design a local strategy to strengthen food sovereignty, the following guidelines will be taken into account to identify key informants:

Its economy depends to a large extent on agricultural or livestock activity.

The unit has been in continuous production for more than three years.

It recognizes agroecology as an alternative method to strengthen food sovereignty.

Once the key informants were identified, we conducted an interview in which we addressed variables such as food sovereignty and its importance and the consequences of its absence, among others.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The interviewee’s accounts revealed about 36 categories of analysis, which were grouped into the following families: concept of food sovereignty, sustainability, technology, challenge and challenges for a program, as detailed below:

Food sovereignty concept family

For the interviewee, food sovereignty is the greatest expression of independence in agriculture and livestock, the process of growing crops to produce food. Then, we need to be self-sufficient and achieve sustenance, not only for the family members but also for the animals. It also highlights the importance of constancy, of producing from an agroecological approach with two diverse connotations and with the least possible use of external inputs (figure 3):

Figure 3. Family concept of food sovereignty

The interviewee’s statement coincides with that of the Via Campesina Movement (2002), which states that it can be said that a people achieve food sovereignty when it prioritizes environmental care and social welfare in food production, rules that the inhabitants of the territory must fully accept. It is for this reason that food sovereignty was associated with access to food and the resources to produce it, as Mr. Zenon relates: “To be sovereign is that here I produce my milk, I produce my eggs, I produce my meat, I produce my vegetables and I do not have to go and consume from outside” (R. Zenon, September 26, 2021; personal communication).

In the same vein, Méndez (2007) emphasizes that being food sovereign also implies ensuring the consumption and commercialization of the surpluses generated in the productive units; as Mr. Zenon says, “there is something more sovereign, it is to have all one’s things here and also take them out of here to sell”....”guaranteeing one’s livelihood at home and guaranteeing the livelihood of many households outwards” (R. Zenon, September 26, 2021; personal communication).

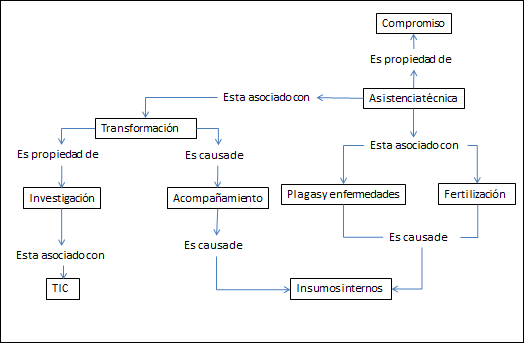

Technology transfer family

According to the interviewee, in order to achieve a technology transfer that allows the strengthening of the food sovereignty of the productive unit, it is necessary to provide committed and qualified technical assistance with techniques or mechanisms emphasized in the control of pests, diseases, and fertilization for which the farm’s internal inputs are used to a great extent. (figure 4)

Figure 4. Technology transfer family

The above is consistent with Montero (2009) who indicates that strengthening is supported by community activities such as commitment, which in this specific case is linked to the producer and especially with the attitude of the person providing the assistance, which is why technology transfer is related to the quality of technical assistance provided, as reported by Mr. Zenon: “Good advice should be taken into account because there are many technicians who come to explain for the sake of explaining and there are people who do their profession just for the sake of doing it” (R. Zenon, September 2021; personal communication). Zenon: “Good advice should be taken into account because there are many technicians who explain just to explain, and there are people who do their profession just to do it” (R. Zenon, September 26, 2021; personal communication). Also, taking into account the concept of strengthening granted for this work in which it is associated with obtaining skills and support material, for this case, it refers to the techniques or mechanisms emphasized in the control of pests, diseases, and fertilization as reported by Mr. Zenon “I would like them to explain processes about fertilizers and insecticides because sometimes you plant a banana and it gets worms or many diseases and you do not know then and it would be good”(R. Zenon, September 26, 2021; personal communication).

Hecht, S. (1999) talks about transforming the productive unit from technology transfer, where the emphasis should be on land use and animal or vegetation management. Palioff, C & Gornitzky, C. (2012). El Camino de la transición agroecológica.) speaks that some processes that characterize this transformation are the advice and accompaniment, that is why technology transfer is related to advice and transformation as Mr. Zenon relates: “a professional technician who comes and tells you to see this is not done this way this is done this way or this way this way you fertilize or this way you do the other thing well For me it would be ideal” ... “We have been doing that, and one has seen the change” R. Zenon, September 26, 2021; personal communication).

Family challenges for a food sovereignty program

The interviewee provides us with some limitations that may arise in programs to strengthen food sovereignty, mainly indicating that sovereignty has a direct relationship with domestic production, and in this, the main challenges are investment and incentives; the interviewee also indicates that when there is internal production in a productive unit, food insecurity, which is related to little knowledge and disorientation due to poor advice, strongly decreases, and also determines that there are cultural factors such as stubbornness that prevent the development of the productive unit as a result of disinterest and lack of adaptation, thus causing unsustainability within the productive unit. (figure 5)

Figure 5. Family challenges for a food sovereignty program

In conclusion, according to the results obtained and the discussions carried out, the design of a strategy for strengthening food sovereignty is conditioned by the degree of independence of the producers, the internal production, the acceptance and commitment of both producers and technicians and the quality of assistance provided by the professionals; therefore, complementarity has been defined as a process that is carried out from within the communities so that they can obtain and manage resources and capacities to achieve collective developments and transformations in terms of their quality of life. This is because when we start a strengthening process, we must know the condition of the community, its degree of organization, participation, and commitment. This strengthening is achieved through self-evaluation methods or using a guided discussion.

REFERENCES

1. Alcaldía. (2020). PLAN TERRITORIAL DE DESARROLLO 2020-2023 “UNIDOS DE VERDAD POR VILLAGARZÓN” (pp. 158–161). Villagarzón.

2. Hecht, S. (1999). Capítulo 1: La evolución del pensamiento agroecológico. Agroecología. Bases científicas para una agricultura sustentable. Ed: Altieri, MA Editorial Nordan Comunidad. p, 15-30.

3. Álvarez, M. R., Zamora, J. I. S., Valenzuela, A. I., & Medina, B. C. (2019). III Taller Internacional de Agricultura Orgánica.

4. Ardila, V. A. (2014). Política nacional de seguridad alimentaria y nutricional.

5. Bravo Bolaños, M. A., & Chicunque, S. P. (2015) Departamento del Putumayo CORPOAMAZONIA.

6. Bringel, B. (2015). Soberanía alimentaria: la práctica de un concepto. Las Políticas Globales Importan, Madrid, IEPALA/Plataforma, 95-102.

7. Burbano Guerra, S. J. (2018). Proyecto Aplicado en la Implementación de Buenas Prácticas de Ordeño en Ganaderías del Municipio de Villagarzón, Putumayo.

8. Ceccon, E. (2008). La revolución verde: tragedia en dos actos. Ciencias, 91(091).

9. Gianuzzi, L., Santarsiero, L. H., Miceli, E. C., Glenza, F. G., Retola, G. A., & Redondi, V. A. (2016). Indicadores para la soberanía alimentaria.

10. Heinisch, C. (2013). Soberanía alimentaria: un análisis del concepto.

11. Hernández Silva, Y. E. (2013). Metodología para la evaluación de la soberanía alimentaria de las familias caficulturas del departamento del Cauca, Colombia (Master’s thesis, Universidad Internacional de Andalucía).

12. Melero Aguilar, N. (2012). El paradigma crítico y los aportes de la investigación acción participativa en la transformación de la realidad: un análisis desde las ciencias sociales. Cuestiones pedagógicas, 21, 339-355.

13. Montero, M. (2009). El fortalecimiento en la comunidad, sus dificultades y alcances. Universitas Psychologica, 8(3), 615-626.

14. Oit, O. I. (2003). Guia Sobre Seguridad y Salud En El USO de Productos de Agroquimicos.

15. Ortega Cerdâ, M., & Rivera-Ferre, M. G. (2010). Indicadores internacionales de Soberanía Alimentaria: nuevas herramientas para una nueva agricultura. Revibec: revista de la Red Iberoamericana de Economia Ecológica, 14, 0053-77.

16. Palioff, C., & Gornitzky, C. M. (2012). El camino de la transición agroecológica.

17. Pinzón Ruiz, N. (2012). Metodología adaptada y conjunto de indicadores para la evaluación de la situación alimentaria de las familias cafeteras Colombianas.

18. Sánchez Gil, H. M. (2018). Seguridad y soberanía alimentaria en la agricultura familiar campesina: el caso de los agricultores de Tibasosa, Turmequé y Ventaquemada, Boyacá.

19. Silva, I. (2017). Metodología para la elaboración de estrategias de desarrollo local.

20. Soares, P., Almendra-Pegueros, R., Benítez Brito, N., Fernández-Villa, T., Lozano-Lorca, M., Valera-Gran, D., & Navarrete-Muñoz, E. M. (2020). Sistemas alimentarios sostenibles para una alimentación saludable. Revista Española de Nutrición Humana y Dietética, 24(2), 87-89.

21. Windfuhr, M., & Jonsén, J. (2005). Soberanía Alimentaria. Hacia la democracia en sistemas alimentarios locales. Heidelberg, Alemanha: FIAN-Internacional e Heifer Internacional.

FINANCING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Herlinton Alejandro Reyes Benavides, Verenice Sánchez Castillo.

Data curation: Herlinton Alejandro Reyes Benavides, Verenice Sánchez Castillo.

Research: Herlinton Alejandro Reyes Benavides, Verenice Sánchez Castillo.

Supervision: Herlinton Alejandro Reyes Benavides, Verenice Sánchez Castillo.

Writing - original draft: Herlinton Alejandro Reyes Benavides, Verenice Sánchez Castillo.