doi: 10.56294/pa202423

ORIGINAL

Effects of hunting and wildlife trafficking by peasants in the Huitorá indigenous reservation

Efectos de cacería y tráfico en fauna silvestre por parte de los campesinos en el resguardo indígena Huitorá

Maria Isabel Garay Monaityama1, Verenice Sánchez

Castillo1 ![]() *

*

1Universidad de la Amazonia, Florencia-Caquetá,Colombia.

Cite as: Garay Monaityama MI, Sánchez Castillo V. Effects of hunting and wildlife trafficking by peasants in the Huitorá indigenous reservation. Southern perspective / Perspectiva austral. 2024; 2:23.https://doi.org/10.56294/pa202423

Submitted: 31-08-2023 Revised: 26-01-2024 Accepted: 16-03-2024 Published: 17-03-2024

ASBTRACT

The following work reflects the activities carried out through the illegal trade of wildlife in the Huitora indigenous reservation, taking into account the hunting and extraction of flora and fauna in said territory, which these activities bring consequences of imbalance in the natural environment.The deterioration of ecosystems. For this reason, a series of interviews were carried out with the inhabitants of the territory and thus be able to know how much affectation is reflected by the peasant in terms of the fall and extraction of fauna, having said that, the wildlife is in danger, for what it is It is important to have the support of the environmental authorities such as the Police Authorities and Urban Environmental Authorities, to fear control in the area, and therefore these wild species have a better life in their natural environment.

Keywords: Hunting; Illegal Trafficking; Control; Extraction; Territory.

RESUMEN

El siguiente trabajo refleja las actividades que realizan a través del comercio ilegal de fauna silvestre en el resguardo indígena Huitora, teniendo en cuenta en la cacería y extracción de flora y fauna en dicho territorio, el cual estas actividades traen consecuencias de desequilibrio en el medio natural y el deterioro de los ecosistemas. Por lo que se llevó acabo una series de entrevista a los habitantes del territorio y así poder conocer que tanta afectación se ve reflejada por campesino en cuanto la caería y extracción de fauna, dicho esto la vida silvestres se viendo en peligro, por lo que es de importancia tener apoyo de las autoridades ambientales tales como las Autoridades policiales Autoridades Ambientales Urbanes, para poner temer un control en la zona, y que por lo tanto estas especies silvestres tengan una mejor vida en su medio natural.

Palabras clave: Cacería; Tráfico Ilegal; Control; Extracción; Territorio.

INTRODUCTION

Wildlife has the freedom to live in peace in their natural environment. However, many of these animals are on the verge of extinction due to illegal hunting and indiscriminate felling of trees, causing various damages and reaching a devastating ecological balance (Ravettino,2018). The countless biodiversity is found in areas such as Indonesia, Australia, Asia, South Africa, Africa, and much of the American continent, making the trafficking of various species in flora and fauna the third illegal trade. South America is the one that moves the trafficking of fauna to about to billion dollars, and its main destinations are Japan, the United States, and Europe, which prefer species such as monkeys, birds, iguanas, and turtles in order to kill and extract the plumage and leather. Brazil is the country with the greatest exploitation, with 12 million victims of wildlife smuggling, with close to 20 percent of animals, and 38 million animals are captured every year, 90 percent of which die in illegal transport and fall. Colombia is the main country with the greatest variety of birds, second in fish, amphibians, plants, third in reptiles, and fourth in mammals. Therefore, this biodiversity is endangered (METROPOLITANA,2019).

Wildlife at the national level is important for rural communities regarding animal protein, with about 27 % of total inhabitants, and in Indigenous people, with 900,000. In the Amazon region, 40,000 tons of meat are extracted (Gómez et al., 1994), which implies the hunting of wildlife, leading to an imbalance in biodiversity.

According to CARACOL RADIO (2017), illegal wildlife trafficking is one of the concerns of the Ministry of Environment, and the departments with the highest illegal wildlife trafficking are Sucre, Caldas, Antioquia, Bolivar, and Cordoba. In the years that more species were seized in 2005 and 2009, rescuing 211,571 animals alive, the most affected by trafficking are the Hicotea turtle, the green iguana, and the barilla, birds such as the parakeet and the parrot, mammals such as the titi monkey, red-tailed squirrel, and the armadillo.

Colombia’s biological diversity is ranked among the first in biodiversity in the world, first in amphibians and birds, and second in flora and butterflies. The diversity in Colombia is converted into illegal hunting and trafficking of wildlife, so it is evident that almost 2000 fauna are in danger of extinction. In Colombia, illegal trafficking affects 76 mammals, nine amphibians, and 234 birds, occupying the second place in illegal hunting and trafficking of wildlife globally (METROPOLITANA, 2019). There are some regulations to carry out the process of control and surveillance, in fact, with the drafting of policies, awareness, and implementation of educational actions. National strategies to prevent and control hunting and illegal wildlife trafficking (Gómez, 2002). This strategy aims to achieve greater conservation of wildlife affected by trafficking and is important for biodiversity.

The Amazon has a great variety of flora and fauna, with about 10 % of biodiversity. Much of this biological reserve is among the seven departments of Colombia, including Caquetá; the wildlife population is found in the Amazonian foothills, valleys, and jungles, as in San Vicente del Caguán, where you can see a variety of animals such as birds, reptiles, mammals and their habitat loss is being caused by indiscriminate deforestation in the Amazon rainforest, reptiles, mammals and their habitat loss is being caused by indiscriminate deforestation in the Amazon rainforest, these species are threatened by unsustainable hunting and illegal wildlife trade, a clear example is the murder of primate mothers (church, marmoset) to sell their offspring (Botache, 2016).

These species are the main ones taken out to the illegal trade in Caquetá such as macaw, royal parrot, eater, churuquero, primates, squirrel monkey, milk drinker, and mammals with food intentions such as boruga, armadillo, cerrillos and wild pigs (Botache, 2016). The authorities confiscate and sanction those who carry out this activity and regulate the trade of these species, avoiding damage to Amazonian wildlife.

However, the interactions of the different ecosystems with anthropogenic activities, such as agriculture, livestock, urbanization, hunting, and illegal trafficking of wild species, have caused the modification, fragmentation, and loss of natural biological systems, with a high cost in terms of biodiversity (Sarukhán et al., 2012).

However, ecosystem changes in terms of anthropogenic transformation, such as cattle ranching, agriculture, hunting, urbanization, and wildlife trafficking, have led to fragmentation, modification, and loss of the natural environment (Galván, 2016).

The HUITORA indigenous reservation has a territorial extension of 67. Two hundred twenty hectares and 89 inhabitants of this community. Since the 1970s, wildlife hunting has been increasing in Resguardo due to many factors, such as The arrival of settlers to exploit rubber, fur sales, timber, mining, and illicit crops. Due to this, the peasants settled around the reservation, opening farms for livestock exploitation, which ended with the forest. Thus, the wildlife. This is why hunting has been occurring on the reservation. Because of this, it is necessary to conserve the wildlife you currently have in the indigenous reservation Huitorá because many species are in danger of extinction, such as the tiger, the tapir, the harpy (golden eagle), Boruga, and the turtle.

The indigenous people of the reserve have been hunting for the sustenance of their families and to have a sustainable life and safe food. The peasants who live around the reserve and have farms nearby took as an alternative economic income hunting and illegal trafficking in order to generate income for their home, causing the decline of mammals, birds, and reptiles being this problem that is taking the reserve causing a shortage of meat for the sustenance of the indigenous people and concern for the fauna in the territory. What are the effects of hunting and wildlife trafficking by farmers in the Huitorá Indigenous reservation?

Theoretical Foundation

Drivers of deforestation

According to FAO (2010), deforestation rates are due to agricultural activities, illicit crops, land speculation, and illegal crops.

Wildlife and illegal trafficking

Finally, wildlife is understood as non-renewable natural resources in Colombia, although defined by Article 249 of Decree-Law 2811 of 1974 of the President of the Republic “By which the National Code of Renewable Natural Resources and Environmental Protection is dictated” (Estrada-Cely et al., 2019).

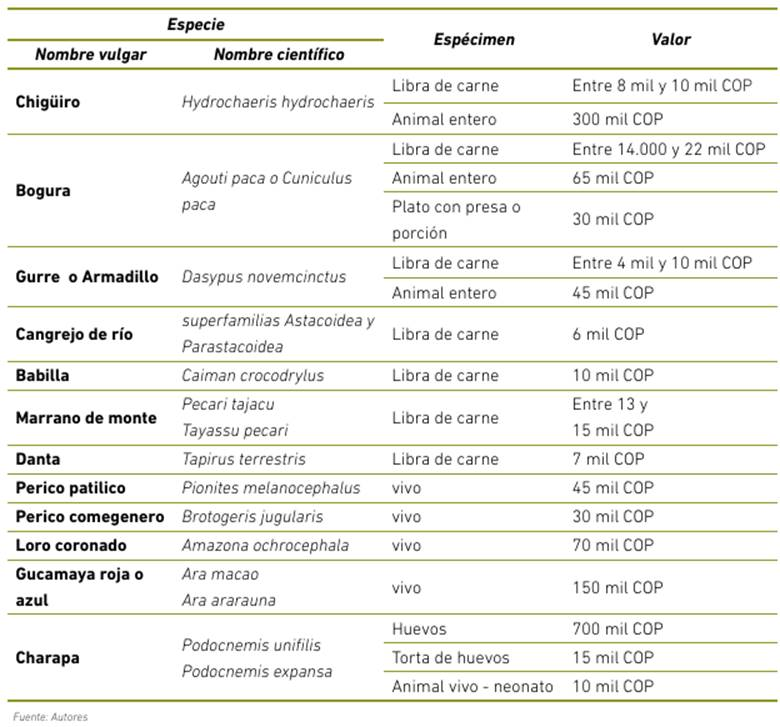

According to Estrada et al. (2019), these resources are mainly directly extracted from the natural environment; however, the territory lacks statistical figures that allow for the certainty of implanting the effect on wildlife and the ecosystem due to its exploitation and illegal business. (figure 1).

Figure 1. Illegal wildlife trade in the department of Caquetá, 2019

Source: (Estrada et al. 2019).

In the department of Caquetá, these crimes are evidenced in terms of its biodiversity for its wild fauna transforming into illegal wildlife trade. This position is reflected in stable seizures made by the environmental commanders to maintain control of this kind of occupation (Estrada et al., 2019).

Conservation strategies

Finally, Law 1333 of 1994 of the Congress of the Republic is the one that constitutes the procedures of environmental authorization and other ordinances similar to Title VI, the placement of wildlife restituted, followed by Article 50, which establishes the preventive seizure and if the authority does not have the necessary spaces for these individuals happen to place them to centers of homes of passage, botanical gardens, and zoos, (Estrada et al., 2019).

In cases quite unusual and without timely penalty damage once the environmental power considers in confiscation wild species which involves large affectations for such subjects supporting technical criteria, that they will be able to access to maintain and conserve continuously and once they are previously inspected against environmental protection followed to that end with the responsibilities and obligations on issues of operation wildlife to maintain (Gov. co, 2009).

Deforestation in the surrounding area

Finally, Sanchez (2020) defines that agro-industries are a threat to agro-ecosystems and also transformed forests into pastures, a problem for Indigenous communities so that these forests have become the home that becomes unrecognizable.

METHOD

Location

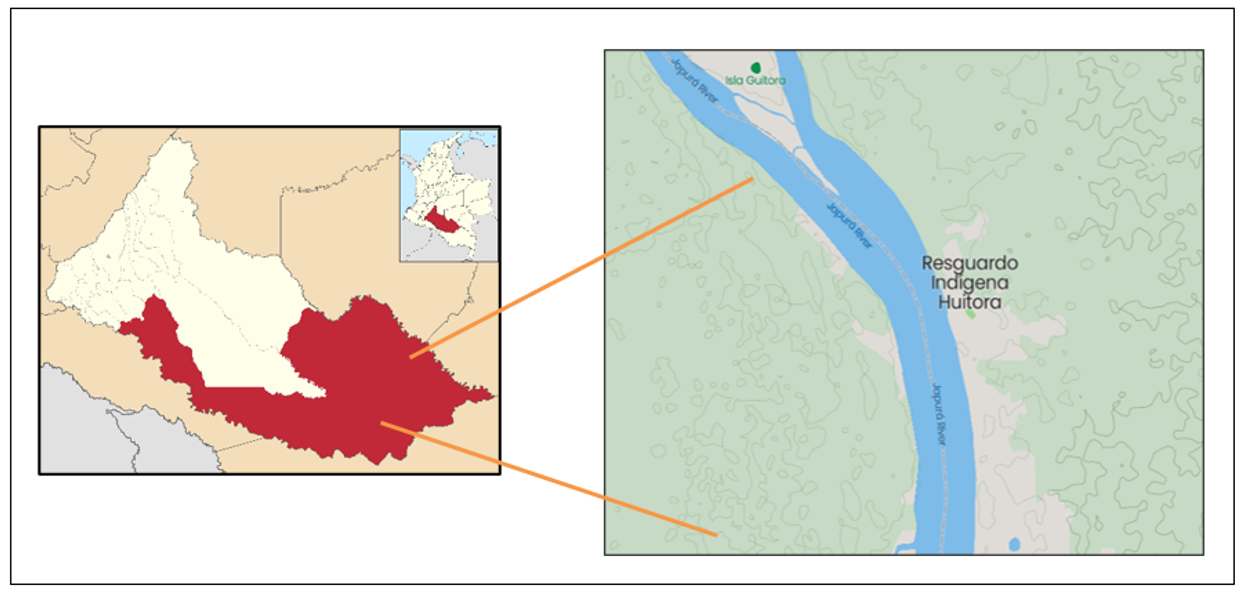

The study site is in the Huitorá Indigenous Reserve of the Solano Caquetá Municipality (figure 2). It has a territorial extension of 67,220 hectares and 89 community inhabitants (Latitude: 0.163156 Longitude: -74.6727). Its boundaries are framed to the north with neighboring settlers and with Tres tronco, La Mana of the municipality of Solano Caquetá; the Huitorá reservation is bordered to the southwest by the Caquetá and to the west by the Orotuya stream and east by the Peneya stream. (USAID, 2013).

Figure 2. Map of the Municipality of Solano, Caquetá (Colombia), Huitorá indigenous reservation

Source: (Mapcarta, 2022).

Population

The population to be studied are the inhabitants of the resguardo, who are adults and minors; the key informants will be the Cacique (head of the resguardo and the knowledgeable of the territory), the governor, and young people who are in the process of leadership for the territory, so they are the ones who have more knowledge in the affectation of hunting and illegal wildlife trafficking. The conditions of the resguardo are the most accurate for carrying out these interviews. This reserve is in the process of biodiversity conservation.

Criteria for the selection of key informants:

· Inhabitants who know all the biodiversity processes that take place in the territory.

· An actor who is directly related to the experience.

· Inhabitants who are in the process of protecting and caring for the wild fauna and flora of the resguardo with institutions.

· Young people play a role in conserving the territory together with ecology.

Research approach

The paradigm of the critical-historical-hermeneutic research. The paradigm introduces fundamentals that are aimed at both symbolic and historical semblance; this method is based on how human nature tries to make sense of a phenomenon that at the same time presents elements of participation, which are manifested in the techniques that are used to use certain information (Arráez et al. de Tovar, 2006).

Descriptive research tries to specify The procedures in science and thus be able to describe the characteristics of the phenomenon between population and subject to be studied and analyzed (Martinez, 2016). This is how it clarifies the effects of hunting and wildlife in the Huitorá resguardo to have an answer on how biodiversity is carried out.

The approach of this research is qualitative because it focuses the study on the quality of relationships and also does not consider the concrete elements of research if not part of the interactions where it relates to the ecology focused on properties and farms in the relation between different elements and guides such studies (Solis, 2019).

Method

A relevant interview was conducted with the key informant of the Huitora Indigenous reservation, following the following criteria:

a) that he/she knew the process in the resguardo from the beginning.

b) that had been maintained throughout the process, a direct relationship in experiences of wildlife trafficking and hunting. Once selected, the informant conducted an interview, which was recorded, then proceeded to pass the interview to Word, made various comments with the keywords, and then passed it to plain text. After this, the plain text was passed using the program Atlasti_22, the phrases of interest were selected, and then the codes were established, which were classified by families, taking into account similarities; the Word cloud was created where the words without major relevance were removed. Finally, the existing codes in each family were established, resulting in a network. Finally, the Sankey diagram was made; therefore, with these data, the description of the findings and the triangulation of the results.

The informant’s name is: The informant tells us that wildlife is affected by hunting and illegal trafficking; the main ones are: Hunting.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

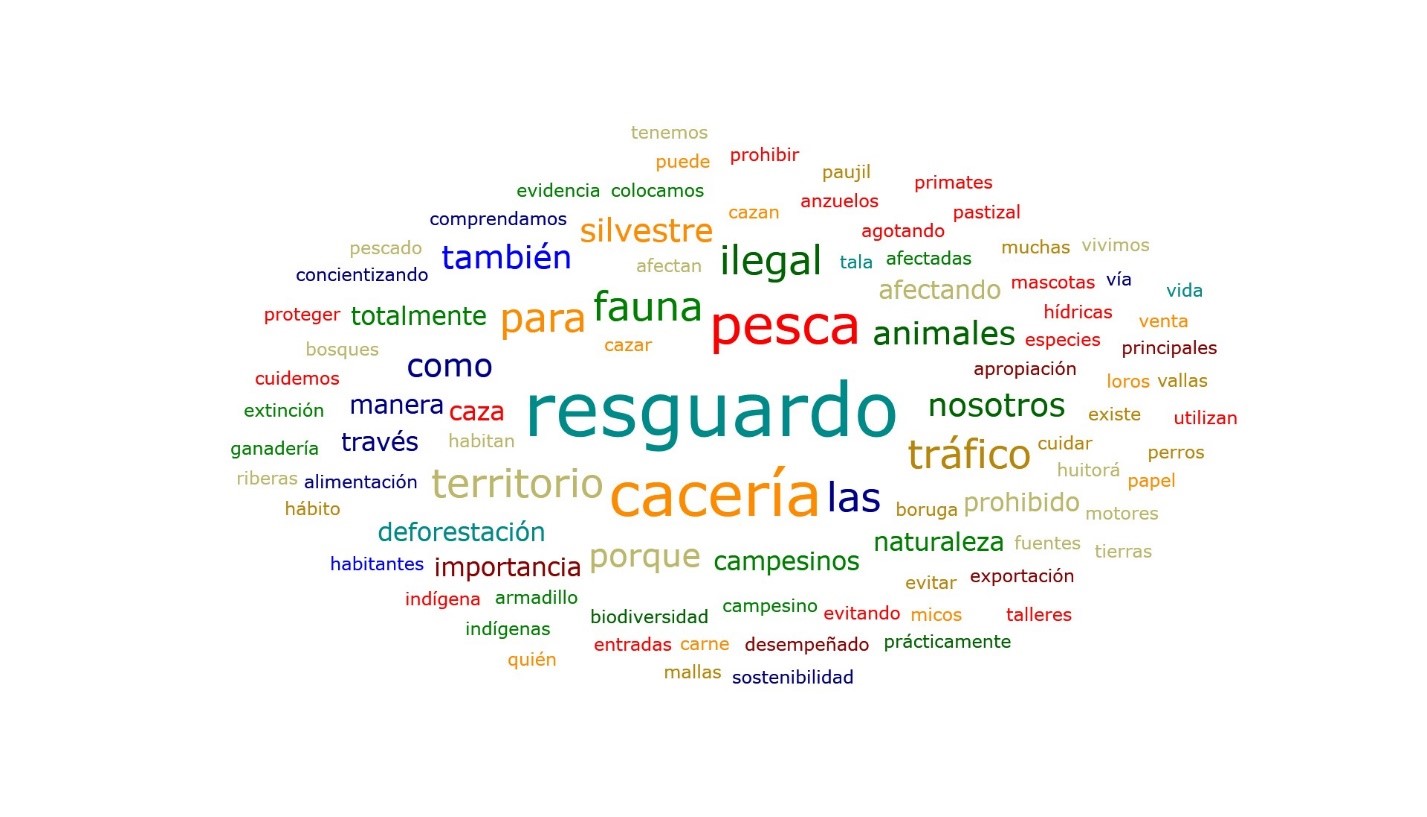

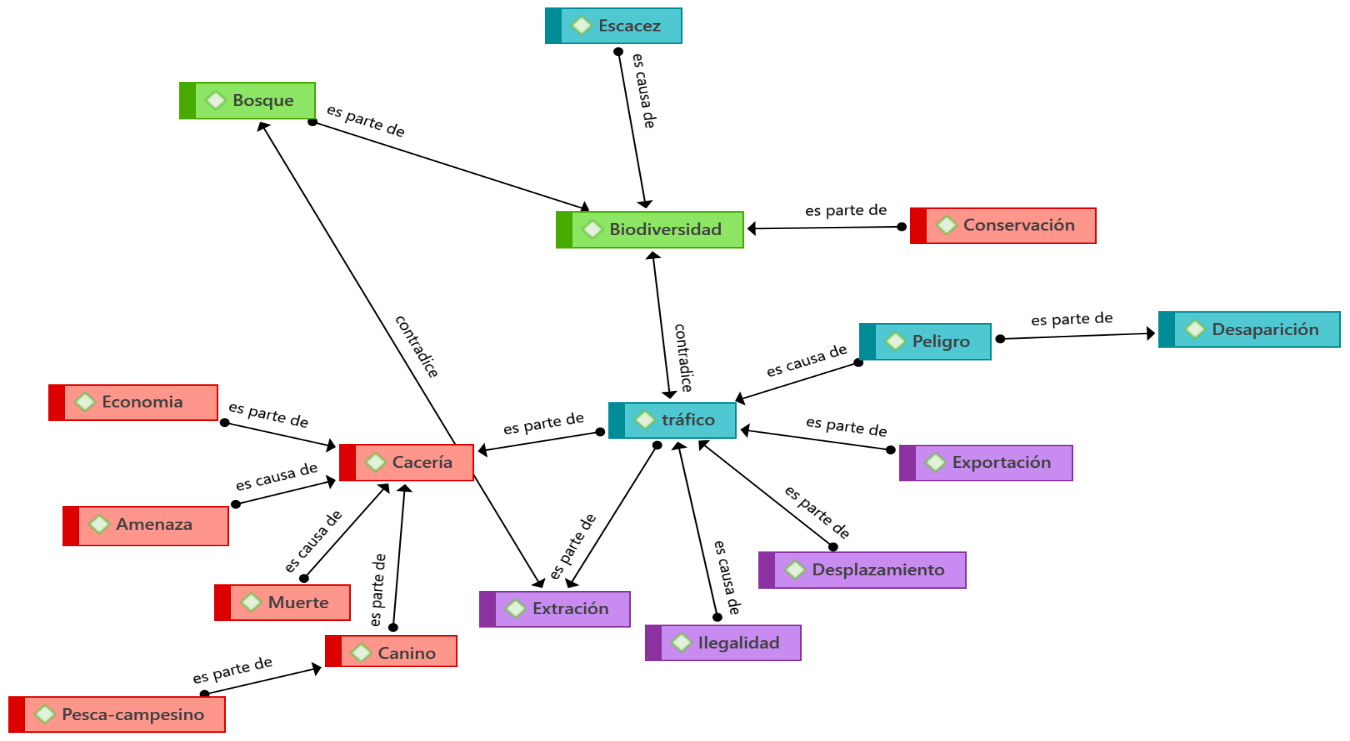

When reading the perception of the interviewees about trafficking and illegal hunting in the Huitora indigenous reservation, it is possible to identify the central axis of people who generate actions against the natural environment, actions such as hunting, illegal trafficking, livestock, logging, fishing caused by the exploitation of natural resources. (figure 3)

.

.

Figure 3. Word cloud around trafficking and poaching, causing damage to natural resources

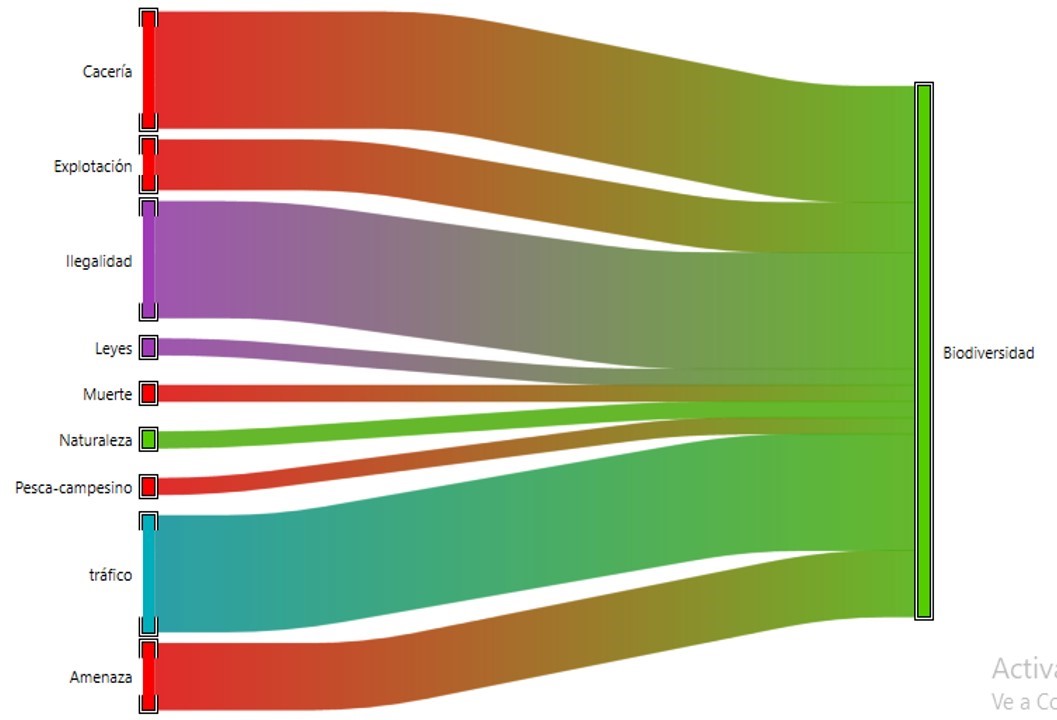

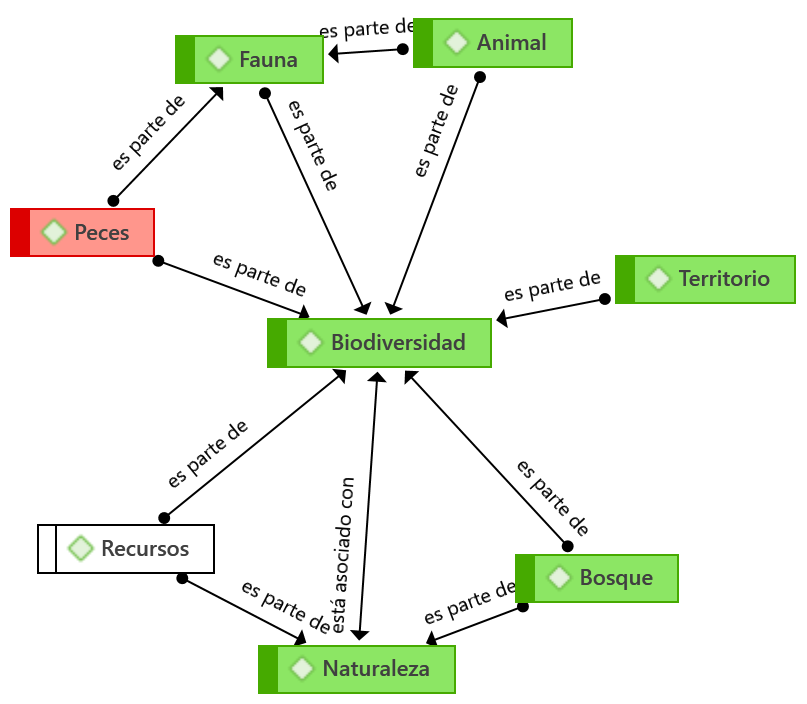

The participants of the interview on trafficking and illegal hunting of wildlife, it is considered that the peasants are the main ones in exploitation and trafficking of wildlife causing deaths in these, and although even less collectively appears the nature society which is important to have a good relationship with nature and the territories, and finally it is evident that in the Huitora indigenous territory there is evidence of affectation in biodiversity in terms of illegal trafficking that is carried out (figura 4).

Figure 4. Sankey Diagram meaning of Biodiversity

Environmental crime

During the interview with the inhabitants, the extraction of wildlife and deforestation of forests by farmers around the reserve was reported, which is used for extensive cattle ranching, cutting down forests for pasture and thus for the appropriation of more land, as well as affecting the banks of the rivers, which is the main cause of displacement of fish. Illegal hunting and trafficking are the main problems in the resguardo and nearby inhabitants of the territory, which is chosen for commercialization and to have an economy and sustainability for their families. In many cases, the exportation of fauna and displacement kills and disappears these species. This affects biodiversity.

For (Retana-Guiascón et al., 2011), wild flora and fauna continue to play a key role in the socioeconomic development of rural groups due to their ability to meet the growing demands for material and cultural goods. However, the problems of forest deforestation, hunting, and illegal trafficking of species by neighboring farmers are of increasing concern to the Indigenous population, as their territory is a thick patch of forest surrounded by extensive areas of pastures for cattle ranching; the reserve becomes precisely the place of habitat for diverse species of fauna, flora, water, and fish, for the self-sufficiency of the Indigenous families of the place, because these extractive activities that turn out to be more of an economic interest than of survival, have as a result that many species die, disappear or are displaced, looking for a safer place (figure 5). According to The Nature Conservancy (2022), throughout history, Indigenous communities have had to put up with peasants entering their territories and carrying out species trafficking, fur trade, illegal logging, mining, uncontrolled extraction, illicit crops, and cultural colonization, among others, which contribute to decrease the territorial autonomy of the Indigenous peoples, which also puts the sustainability of local families at risk.

Figure 5. Environmental crime

Wildlife

Wildlife evolved in the United States of America in the 20th century and in England as a “game species” (O, 2011). Wildlife is important for the natural environment and people, contributing to the service of the environment and natural resources, which refers to living, non-domesticated beings (Manejo de vida silvestre, 2022). The approach of the national policy on wildlife, the authority followed by Article 15 of the General Law of Ecological Balance and Environmental Protection, so that the authorities must take preventive measures in genetic conservation, and restoration, protection of the natural environment of these species, also for the recovery and conservation in wildlife (Leon, 2018) (figure 6).

Figure 6. Wildlife

CONCLUSIONS

Animal trafficking and hunting are some of the most abundant activities in Indigenous territories; these activities create serious problems in terms of the balance of natural resources that can end up with the extinction of different species; many of these businesses cause the death of wild species, so laws have been made to protect these species and can be in their habitat and thus preserve the biodiversity of the territories and Indigenous reserves.

REFERENCES

1. Arráez, M., Calles, J., & Moreno de Tovar, L. (2006). La Hermenéutica:una actividad interpretativa*. Sapiens. Revista Universitaria de Investigación, 8-12.

2. CARACOLRADIO. (2017). El TOP 5 de los departamentos donde más trafican especies. Obtenido de https://caracol.com.co/radio/2017/04/13/regional/1492043908_900585.html

3. Estrada-Cely, G. E., Guzmán-Ríos, M. A., & Parra Herrera, J. P. (2019). Estado actual de la fauna silvestre posdecomiso en el departamento del Caquetá - Colombia. revistamvz@ces.edu.co.

4. Galván, S. G. (2016). Día Nacional de la Conservación. GACETA: LXIII/2PPO-59/67672.

5. Gov.co. (21 de julio de 2009). Ley 1333 de 2009. Obtenido de https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/gestornormativo/norma.php?i=36879

6. Gómez, M., R. Polanco y A. Villa. 1994. Uso sostenible y conservación de la fauna silvestre en los países de la cuenca del Amazonas. Colombia. En: Informe para la FAO. Santafé de Bogotá. 86 p.

7. Leon, E. Z. (19 de Enero de 2018). LEY GENERAL DE VIDA SILVESTRE. Obtenido de https://www.senado.gob.mx/comisiones/medio_ambiente/docs/LGVS.pdf

8. METROPOLITNA. (2019). COLOMBIA: NUESTRA RIQUEZA TAMBIÉN ESTÁ AMENAZADA. Obtenido de FUTURO SOSTENIBLE: https://www.metropol.gov.co/Paginas/Noticias/elmetropolitano-ambiental/colombia-nuestra-riqueza-tambien-esta-amenazada.aspx

9. Manejo de vida silvestre. (2022). Obtenido de FAO: https://www.fao.org/sustainable-forest-management/toolbox/modules-alternative/wildlife-management/basic-knowledge/es/

10. Martinez, C. (20 de Septiembre de 2016). Investigación Descriptiva: Tipos y Características. Obtenido de StuDOCU: https://www.studocu.com/co/document/universidad-antonio-narino/metodos-epidemiologicos/investigacion-descriptiva/28012916

11. O, L. J. (2011). LA INVESTIGACIÓN EN TORNO A LA CONCEPCIÓN DE VIDA SILVESTRE:. Bogota-Colombia: file:///D:/Downloads/monitorbio,+BIOARTICULO+4.pdf.

12. Retana-Guiascón, O. G., Aguilar-Nah, M. S., & Niño-Gómez, G. (2011). USO DE LA VIDA SILVESTRE Y ALTERNATIVAS DE MANEJO INTEGRAL. EL CASO DE LA COMUNIDAD MAYA DE PICH, CAMPECHE,. Tropical and Subtropical Agroecosystems, 2.

13. Sánchez, J. S. (03 de Febrero de 2020). Los riesgos que enfrentan las comunidades en la frontera de la deforestación en Colombia. Obtenido de The Nature Conservancy: https://www.nature.org/es-us/sobre-tnc/donde-trabajamos/tnc-en-latinoamerica/colombia/historias-en-colombia/riesgos-comunidades-deforestacion-en-colombia/#:~:text=Comercio%20de%20pieles%2C%20tr%C3%A1fico%20de,territorial%20de%20los%20pueblos%20ind%C3%ADge

14. Solís, L. D. (28 de mayo de 2019). El enfoque cualitativo de investigación. Obtenido de Investigalia: https://investigaliacr.com/investigacion/el-enfoque-cualitativo-de-investigacion/

FINANCING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Maria Isabel Garay Monaityama, Verenice Sánchez Castillo.

Data curation: Maria Isabel Garay Monaityama, Verenice Sánchez Castillo.

Research: Maria Isabel Garay Monaityama, Verenice Sánchez Castillo.

Project administration: Maria Isabel Garay Monaityama, Verenice Sánchez Castillo.

Resources: Maria Isabel Garay Monaityama, Verenice Sánchez Castillo.

Supervision: Maria Isabel Garay Monaityama, Verenice Sánchez Castillo.

Writing - original draft: Maria Isabel Garay Monaityama, Verenice Sánchez Castillo.